Crackers have been a traditional part of British Christmas festivities and other celebrations since Victorian times. The most widely accepted story is that they were invented in the mid-1840’s by a London pastry cook named Tom Smith, who came upon the idea while on a trip to Paris where he witnessed the French holiday custom of wrapping sugared almonds and other sweets in a twist of colored paper. Smith included a romantic message in his early crackers which he marketed in Britain as “Kiss Mottoes”. However the product enjoyed only limited success until Smith devised a way to make the cracker “pop” when pulled apart. Want to know more? The following paragraphs summarize the History of Christmas Crackers, particularly some important milestones in the development of this product in England.

What are Christmas Crackers?

A Christmas Cracker is a type of party favor originating in England, but now widely used throughout the modern world to celebrate Christmas and other special occasions and festive events. They consist of a wrapped and decorated cardboard cylinder and very much resemble a large candy twist. Crackers typically contain a paper crown (tissue party hat), a motto (joke or riddle), a snap (friction activated popping device), and a small gift or novelty item. Crackers provide a colorful and exciting start to any celebration, and also present each guest with a gift by which to remember the days events.

Crackers are usually shared between two individuals, often with the arms crossed, one pulling on each end. With the ends firmly gripped, the cracker is slowly pulled apart using steady pressure and a twisting motion. This will tear the cracker open along one or both gathers, activating the “cracker snap,” and producing a small **BANG**.

Crackers are typically used to decorate individual place settings and are often opened prior to serving a food or refreshment course. At Christmas, crackers also make great tree ornaments, stocking stuffers, and welcoming gifts for visiting friends and relatives. Other uses include invitations, promotional and corporate gifts, advertising media, shower and wedding favors, and personalized gifts for special occasions such as Valentine’s Day and Mother’s Day.

There is an abundance of information available on the internet to assist you in making your own crackers. You can buy kits which have all the materials included , or you can purchase the individual components (wrapping paper, cardboard tubes, tissue hats, snaps, mottoes, etc.) from online stores such as Olde English Crackers. Making crackers is a wonderful holiday craft project and something that will be new and exciting to many who give it a whirl. It is also possible to purchase crackers that you fill yourself for those of you who wish to personalize the gift contents of the cracker. These crackers come fully assembled but open at one end and complete with hat, snap and joke. All you have to do is add the gift and tie the cracker shut to finish it.

For additional information on making and using crackers, including links to useful Do It Yourself sites and How To videos, we recommend you visit our All About Christmas Crackers web page. Now onto the History lesson.

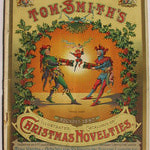

The Tom Smith Story

The Early Years

As a young boy, Tom Smith worked in a bakery and confectionery shop in London. He was especially interest in the wedding cake decorations and experimented in his spare time with new, creative designs. Before long he was able start up his own business in Goswell Road, Clerkenwell, East London. In 1840 Tom traveled to Paris where he discovered the ‘bon bon’, a sugared almond wrapped in a twist of tissue paper. He decided to bring the ‘bon bon’ to London and during Christmas that year they sold extremely well. However in January demand virtually ceased and once again he was reliant on sales of cake and table decorations.

In an effort to further develop the ‘bon bon’ idea, Tom decided to place a small love motto in the tissue paper. He was able to successfully market these to many of his regular customers and as sales and his profit continued to increase he knew that he had come upon a unique and potentially valuable new product. He decided to continuing developing his new ‘bon bon’ product while still running the wedding cake ornament and confectionery business which was by now very well established.

At this time, the majority of ‘bon bons’ were still being sold at Christmas so Tom focused on this short but very profitable season and how he might make his ‘bon bons’ even more appealing. It was the crackle of a log in his fire one day that gave him the inspiration which eventually led to the cracker as we know it today.

From ‘Bon Bon’ to ‘Cracker’

The crackle from a burning log gave Tom the idea to add the element of sound to his novel ‘bon bon’ product. It was now simply a matter of experimentation to find a mechanism which would produce a satisfactory ‘bang,’ ‘crackle’ or ‘snap’ without going to far into the world of explosive devices. The size of the ‘bon bon’ would also need to increase significantly to accommodate the sound producing device but the shape would remain the same and the motto would of course still need to be included.

Tom eventually fell upon the idea of incorporating a friction activated chemical explosion into his product to produce the necessary ‘popping’ sound. The chemical was silver fulminate, a compound discovered by the English chemist Edward Charles Howard (1774 – 1816) in 1800 and further developed in 1802 by the Italian chemistry professor, Luigi Valentino Brugnatelli (1761 – 1818). This eventually became the cracker snap of today and Tom Smith’s Christmas Crackers were born.

The incorporation of the snap lead to an immediate jump in sales and Tom’s business was snowed under with orders. He quickly refined his new product dropping the ‘bon bon’ name and calling his new crackers Cosaques to which he added a surprise gift. Tom soon decided to explore the export market and took his cracker abroad. After a foreign manufacturer copied his initial cracker design and delivered a consignment of crackers to England for the upcoming holiday season, Tom immediately designed 8 different kinds of cracker and distributed stocks throughout the country also in time for Christmas. After this he never looked back. Tom Smith lived to see the new branch of his firm grow to swamp the original premises in Goswell Road, but passed on March 13th 1869, probably from stomach cancer, at the young age of 46.

When he died he left the business to his three sons, Tom Henry and Walter. A few years later, a drinking fountain was erected in Finsbury Square by Walter Smith in memory of his mother, Mary, and to commemorate the life of the man who invented the great British Cracker.

Continuing the Legacy

After his death Tom Smith’s three sons took on the task of developing new cracker designs, contents and mottoes. Walter Smith, the youngest son, introduced a topical note to the mottoes which had previously been love verses. Special writers were commissioned to compose snappy and relevant maxims with references to every important event or craze at the time from greyhounds to Jazz, Frothblowers to Tutankhamen, Persian Art to The Riviera. The original early Victorian mottoes were mainly love verses but these were eventually replaced by more complicated puzzles and cartoons, and finally by the corny jokes and riddles which characterize the crackers of today. Walter also introduced the paper hats, many of which were elaborate and made of the best tissue and decorative paper on proper hatmakers stands.

Walter Smith also toured the world to find new, relevant and unusual ideas for the surprise gifts such as bracelets from Bohemia, tiny wooden barrels from America and scarf pins from Saxony. Some contents were also assembled in the factory like thousands of tiny pill boxes filled with rouge complete with powder puff.

The Tom Smith Company was now able to fulfill special orders for both companies and individuals. Records show an order for a six foot cracker to decorate Euston Station in London, and in 1927 a gentleman wrote to the company enclosing a diamond engagement ring and 10 shilling note as payment for the ring to be put in a special cracker for his fiancee. Unfortunately he did not enclose an address and never contacted the Company again. The ring, letter and 10 shilling note are apparently still in the companies possession today.

Into the 20th Century

At the turn of the century the cracker industry in England was booming. The Tom Smith Cracker Company was produced crackers not only for the Christmas season but also to celebrate every major occasion from The Paris Exhibition in 1900 to War Heroes in 1918 and The World Tour in 1926 of Prince Edward, The Prince of Wales. Contents were tailored to each box and included artistic masks, puzzles, conundrums, tiny treasures, jewels, games and mottoes. Perhaps most notable of this era was that most the beautifully illustrated boxes, crackers, and hats were made by hand. The fully illustrated catalogs which date back to 1877 provide an exceptional visual history of British social and political development over an entire century.

In the early days Tom Smith specialized in producing high end exclusive crackers, including Wedgwood Art Crackers from original designs by permission of Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, and designs such as Japanese Menagerie crackers containing the latest novelties from Japan. These include animals, birds and and reptiles and even mottoes in Japanese. The company was, importantly, very aware of current affairs and the political and leisure activities of each period. Crackers were created for the War Heroes, Charlie Chaplin, The Wireless, Motoring, The Coronation, The Channel Tunnel, Radio, Aviation, Votes for Women, Suffragettes, The Postal Service, Cycling, Scouting, The Paris Exhibition., and even the Channel Tunnel in 1914. Exclusive crackers were also made for members of the Royal Family and still are to this day. The Tom Smith Group Limited have held 6 Royal Warrants to produce Christmas crackers since the turn of the 20th century. The first was granted to the Prince of Wales in 1906. The company still holds two of these warrants, one granted to Queen Elizabeth II in 1964 and the second to the Prince of Wales in 1987 to produce special crackers for the Royal Household.

During the Second World War, cracker production was banned by the government of the day, perhaps as a means to save money but also to implement a troop training method where the snaps (exploding part of the cracker) were used to imitate gun fire! After the war, vast quantities of surplus cracker snaps were released back into the cracker trade. As the demand for crackers grew again, Tom Smith merged with Caley Crackers in 1953 moving from their Wilson Street operation at Finsbury Square in London and taking over the Caley headquarters and factory in Norwich, East Anglia. Further merges took place over the following years with Mead and Field, Neilson Festive Crackers and Manson and Church, each specialists in their own particular field.

In 1963 Tom Smith’s Salhouse Road factory caught fire, the third fire in their history, including one in the 1930’s and another in the 1941 Blitz of London. The company managed to survive and produced crackers again until the 1980’s at which time they were employing a combined total of some 500 people in their Norwich and Stockport factories and producing in the region of 50,000,000 crackers per year. In the late 1980’s the company had a management buyout, but unfortunately was not able to continue in an independent state and in 1998 it was bought out by Napier Industries. Sadly this too came to an end and today crackers made under the brand name of “Tom Smith” are produced by Brite Sparks who are owned by International Greetings Plc.

For additional information about Tom Smith and the History of the Cracker industry in England we strongly recommend Peter Kimpton’s website The King Of Crackers. As a former employee of Tom Smith’s he has written a fascinating book full of interesting facts and speculations, accompany by wonderful illustrations of the time. A number of the images accompanying this article were made available by permission of Peter Kimpton, renowned Christmas Cracker historian and owner of The Kathleen Kimpton Collection.